Like most, I had trouble fitting in growing up. And I think I can point to a few reasons. Half my family were Yankees, which can still be an issue in deep areas of the South. My closest relative in age was my mom's brother, as I was an only child on both sides of the family. And I had an offbeat sense of humor that was bred from watching Monty Python movies by myself at a time in my development that was too early for most. Neighbors were few and far between, as my father would not live in town. You see, we were social distancing even back in the '80s. So, the combination of rural living and the generation gap accounted for some weirdness that, in retrospect, I can look back on and appreciate, but “geek” was not a badge of honor one would self-apply, especially during the Reagan years.

Solace, from the pangs of awkwardness growing up, came in the form of elementary school Halloween, where a great costume could buy you credit with your classmates. That’s why in first grade, I was Yoda. Second grade, I was Dracula. But in third grade, my trip up the social ladder hit an obstacle called my mom’s sensibilities.

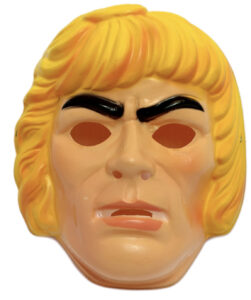

You see, Mom wasn’t a fan of the store-bought costumes. You know, the kind with the plastic vacuform mask, the ones that had the little slit in the mouth so you could breathe, but by the end of the night, your face was resting in a swamp of its own juices. And they usually came paired with a plastic smock that had whatever character’s body printed on it. See, nothing said “strength” like an eight-year-old with He-Man’s chiseled six-pack. But as I had no money or a trip to Kmart, what’s a kid to do except concede to his mother’s wishes?

She went to work putting my costume together with props around the house. She found a black and white striped T-shirt, a black beret, my great-grandmother’s white gloves, and last year’s black-and-white Dracula makeup. And she put it all together. I got dressed, stepped in front of the mirror, and said:

“Mom, what am I supposed to be again?”

And then she proudly said, “You're a mime.”

I spent the rest of the day explaining to everyone that a mime was a performer who didn’t speak. And yes, I know even then, that this was ironic.

By the end of the day, the makeup on my face had smeared and started to fade in. I’m sure it was a fright, the living embodiment of a black-and-white cartoon in a full-color world. And I’m sure it made people uncomfortable because they didn’t know what a mime was.

One heckler on the playground ran up to me and said, “I don’t think I like mimes.” And he punched me straight in the gut.

Luckily, the next year, I changed to a new school in a different town because my mom became a teacher there.

When I brought up this pseudo-painful experience to my mom, she said she didn’t remember it. And she even went as far as to say that perhaps dressing up as a mime was my idea.

Right, Mom. It was me, an eight-year-old, who, instead of dressing as He-Man, decided to go to his country school dressed as a French clown.

By ninth grade, I had started going to high school in my hometown again, and out of self-preservation, I decided to keep my head down. By the end of 10th grade, I had become friends with Matt. Matt was tall. He was smart. He had hair like a bright red Brillo pad. He had a very thick country accent, and we shared the same offbeat sense of humor. His favorite movie, in fact, was Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

Like me, he also liked Halloween. See, I finally felt like I had made that friend. All through the rest of high school, Matt and I would hang out on the weekends. We’d go to the movies, watch Saturday Night Live when we could, and quote it badly, too. We’d play board games and basically just hang out.

Our parents were so glad we were friends because we weren’t the kind of kids who were out drinking or getting high. And because we were veritable wallflowers, there were no high school pregnancy scares. Even during my senior year, the first person I visited after one particularly bad date was Matt, who happened to live across the street from her.

“How’d it go, man?”

“Well, it went pretty good until the end. You know, I don’t know how to end a date.

“You know that thing in my house that I say to my parents every night? The thing that I’ve said to them since I was a little boy? Well, I said it to her by mistake.

“She was getting out of the car, and I didn’t know what to do, and I got so nervous. So I turned and I said, ‘Good night. I love you.’ And then I tried to recover and said, ‘Oh, no, I don’t love you. I mean… maybe one day I could love you.’”

I don’t think there’s gonna be another date.

In our 20s, on one particular Halloween, I went over to Matt’s in the evening and knocked on the door. I heard:

“Hold on a minute, man. Let me get my hat.”

Then Matt appeared in the doorway. He stood there, stock still, at attention, with his hands by his side. He was wearing a yellow sweatshirt and matching yellow sweatpants, tan socks, and patent leather black shoes. His "hat" was colander with a pink pillow glued to the top. The last accessory to his costume was the number 2, stenciled on his chest with black spray paint.

In his thickest accent, Matt said, “Hey man, what am I supposed to be?”

I said, “You’re a pencil.”

“Man, you’re the only person who got that all day. Do you know what it’s like when nobody gets your costume?”

And I said, “Sure I do. Do you know what a mime is?”

By the time we were in our 30s, Matt and I didn’t see each other as much, which was natural. We lived in different parts of the state. We both had families, and when we did visit our hometown, it was usually on different weekends. But we tried to keep in touch with phone calls and the occasional email. I always figured that Matt and I would be friends into old age.

Well, one day, after leaving a protest here in Huntsville that campaigned for the removal of a Confederate statue at the courthouse square, I was feeling frustrated and motivated. So I decided to reach out to Matt via email to see if he would advocate for the removal of such symbols in the public spaces where he lived.

Now, I was sure there would be a little pushback, as I was well aware of the attitudes in our hometown and the fact that his family had been there for generations. But, if I’m being honest, it was kind of a small ask.

To my surprise, the virtual back-and-forth went on for several days. And in that exchange, something miraculous happened.

For so long, I had been the one wearing a certain type of mask. I had grown used to hiding aspects of myself that I knew separated me from the people in my hometown, simply to fit in, even from Matt. But I was now fully comfortable in my beliefs.

I ended the thread with a didactic “high road” quote, which was meant to put a pin in things, but unknowingly it became the nail in the coffin.

The response I got from Matt was absolute vitriol. Matt was unwilling to recognize that any opportunities in his life, and any privilege that he had, were in part due to the fact that his skin happened to be white.

And this was a fact that I was not willing to let go or or give a pass to. But this was a conversation we were going to have to have if we were to remain friends in any fashion.

As we couldn’t find a path forward, I think we both knew this would be our friendship’s resignation.

Whereas my mask had faded away from having moved so often and met so many different kinds of people, this was the first time I had to remove someone else’s to see them clearly.

And even though it wasn’t a death, I still mourned the end of it.

Here’s the deal: I’m not the kind of person who would try to rewrite the past because of how things ended. Our friendship was too formative, too good at times. And the lessons we’ve learned from our past are what make us who we are now.

I think back to one of the best times we had together. It was emblematic of our whole friendship because it was fun and off-kilter.

It was Halloween, and I’m pretty sure it was the one right after that very bad date. Matt and I were way past the age of trick-or-treating, but we still wanted to have some fun.

So we went into his parents’ garage and found his dad’s gardening equipment. We found two matching pairs of coveralls, ski masks, glasses, gloves. We covered ourselves up and went to the front yard with two folding chairs. We set up with a little table between us, a bowl of candy, and a homemade sign that said:

Free candy, if you dare!

Kids would walk up and hesitantly look around for a moment before reaching in. A hand would go in... and bam, we’d grab it. We never had so much fun making children cry.

After about three hours, we’d had our fill, and the joke had worn thin. Kids who had been really scared would run back and warn the approaching trick-or-treaters about the gangly scarecrows.

While lifting his ski mask, Matt asked, “Ready to call it a night?”

To which I replied, “Sure am.”

Knowing that circumstances would separate us in the end, I might not have been so quick to end that evening, an evening before our future selves had been revealed.

I can imagine that same Halloween, after scaring several kids, Matt starts to lift his mask.

“Ready to call it a night?” Matt would ask.

To which I would reply:

“No, man. I’m having a good time right now. Let’s leave our masks on a little longer.”